Red Sea Doctrine: Littoral States Shut the Door on Expansionism

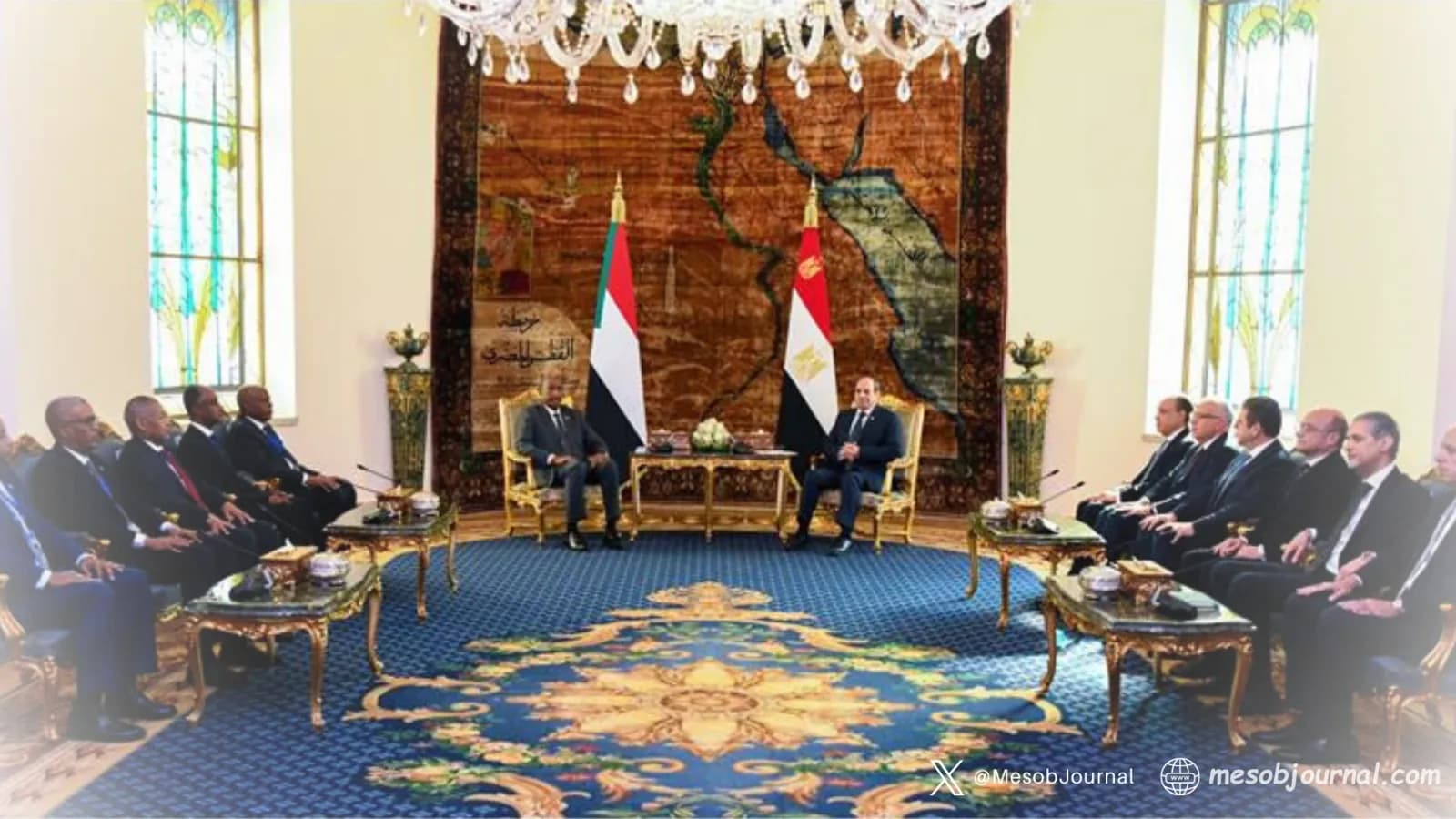

Cairo was more than a ceremonial trip. When Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki stood beside President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi this November, the message wasn’t about museums or optics — it was a map of how the Red Sea will now be governed.

No slogans. No ambiguity. A littoral doctrine is taking shape, and the region is quietly uniting around it.

The Horn speaks for itself

In his interview after the Cairo visit, President Isaias cut through years of noise. The Red Sea, he said, cannot be outsourced. Each coastal nation must build its own capacity to secure its waters, cooperate with neighbors, and reject foreign bases that turn sovereignty into rent.

If, and only if, the region needs support, it should come through a legal framework blessed by all — not through back-door deals with powers chasing influence. It’s a principled stance, but also a practical one: the security of this corridor depends on the discipline of those who live by it.

This isn’t a new improvisation. Eritrea has already tabled a detailed twelve-point proposal — a structured plan that revolves around sovereign capacity-building, collective coordination among littoral states, and clear legal boundaries for any external role. The plan envisions the Red Sea as a cooperative security space, free of foreign bases and governed by the nations that share its shores.

Eritrea’s framework has now become the reference point. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and others are aligning with what Asmara had articulated years earlier — that the Red Sea’s stability must come from within, not from the agendas of external patrons.

Cairo, Djibouti, and the new map of logistics

At the same time, Egypt and Djibouti are building the hardware for this new order. Djibouti’s ports authority has confirmed a major agreement with Egypt’s Elsewedy Electric — a ten-hectare logistics hub inside the free zone and a 1.5-kilometer quay dredged to −18 meters.

It’s not a ribbon-cutting gesture; it’s the literal steel and concrete of regional autonomy. A future where African ports trade capacity among themselves rather than lease sovereignty to outsiders.

The timing isn’t coincidence. Addis Ababa’s leadership has recently flirted with a dangerous narrative — claiming that “Afar Ethiopians have a right to the sea,” a statement that unsettles Djibouti, itself home to a large Afar population and the country most directly targeted by such rhetoric. For Djibouti, this isn’t theory; it’s geography under threat. And for Egypt, which already faces unilateral dam policies upstream, the signal is the same: unchecked expansionism anywhere along the Nile-Red Sea axis endangers everyone.

Seen through that lens, the Djibouti-Egypt partnership is not just economic; it’s defensive diplomacy cast in infrastructure. When you connect it to the Cairo doctrine, it’s obvious: regional self-reliance is moving from speech to structure — from joint statements to cranes, steel, and sovereign waters.

The sea drills, the message drills deeper

While politicians met in Cairo, Red Wave 8, the Egyptian-Saudi naval exercise, kicked off in the Red Sea — a show of interoperability that quietly reminds everyone who actually secures these waters.

For years, the Red Sea has been overcrowded with flags — foreign patrols under the guise of “stability” and their client states. But now, regional navies are beginning to define stability on their own terms. The symbolism couldn’t be clearer: maritime guardianship belongs to the shores, not to passing fleets.

Addis meets a wall of law

For months, Addis Ababa’s rhetoric has revolved around “historical rights” and “access by all means” — in other words, ownership of ports it once occupied through war. But as it doubles down on threats, the neighborhood is closing ranks.

Somalia rejected Ethiopia’s illegal MoU with Somaliland as a sovereignty breach. Russia’s ambassador in Addis reminded that any sea-access issue must be resolved through mutual agreements under international law — a stance now echoed by the European Union and the United States, which have both stressed the primacy of legality and regional consent.

And like Eritrea, Egypt’s foreign minister has drawn the line clearly: the Red Sea’s governance belongs to its littoral states, not to landlocked adventurists.

Ethiopia’s expansionist fantasy is colliding with a wall of coordination — a unity it never expected, and cannot intimidate.

Sudan, Somalia, and the wider horizon

The same logic applies inland. The Sudan crisis, as the President of Eritrea explained, isn’t a civil war but a conspiracy of external manipulation. The neighbors — Egypt, Eritrea, and those genuinely close to Sudan — insist that the solution must be Sudanese-owned.

And in Somalia, the task is capacity-building, not occupation. No one can defend Somalia’s more than 3,000-kilometer coastline better than Somalis themselves. Eritrea’s support has always aimed at that — patient, grounded, and free of the mercenary shortcuts that ruined the past.

A closing current

Step back and the dots connect themselves. Cairo hosts the doctrine. Djibouti builds the docks. Saudi drills at sea. Eritrea defines the blueprint and principle. And every move narrows the space for external powers — and their clients like Ethiopia — to posture.

What’s forming is not a bloc but a balance — a maritime compact rooted in sovereignty, law, and cooperation. It doesn’t seek confrontation; it seeks clarity.

The Red Sea, once treated as a playground for outsiders, is being reclaimed by its own shores. And that, in every strategic sense, is the quiet revolution President Isaias described: the Horn of Africa governing itself — by right, by law, and by will.

Related stories

Eritrea Draws a Legal Red Line on Ethiopia’s “Sea Access” Drumbeat

On Thursday Jan. 30 2026, Eritrea's Information Minister Yemane G. Meskel cut through weeks of Addis Ababa’s noisy “sovereign sea access” messaging with a blunt reminder: access to ports is commerce and transit — not entitlement, not “historical destiny,” and not a blank cheque f

Somalia Scraps UAE Security Deals as Regions Push Back

Somalia’s Council of Ministers has formally terminated all bilateral security and defence agreements with the United Arab Emirates, marking one of the most consequential foreign-policy moves taken by the federal government in recent years. In a cabinet decision adopted on Sunday,

Sudan at the Crossroads: A Peace Initiative Rooted in Accountability, Not Illusions

Sudan is not asking the world for sympathy. It is asking for seriousness. That message came through clearly at the United Nations on Monday, as Sudan’s Prime Minister laid out a peace initiative framed not as a pause in violence, but as a realistic, enforceable exit from war . I

Egypt: Cairo Draws Clear Red Lines as Sudan’s War Tightens Its Grip

Cairo didn’t dress it up in diplomatic fluff. In a sharply worded statement issued during General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan’s one-day visit, Egypt’s presidency laid out a position that is as much about Sudan’s survival as it is about Egypt’s own security. The message was blunt: Suda