Ethiopia’s Costly Choice: How Political Arrogance Cut Addis Off From the Red Sea

For years, Ethiopian officials and state-aligned media have repeated a striking claim — that the country spends enormous sums each year on port access through Djibouti because Eritrea allegedly denied it a route to the Red Sea. The narrative, now echoed across speeches and social platforms linked to Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s government, portrays Ethiopia as a victim of geography.

But archival records and international documents tell a different story. Ethiopia once had full, tariff-free use of Eritrea’s ports — and abandoned them by choice.

A free port unlike any other

After Eritrea’s independence in 1993, the port of Assab became Ethiopia’s maritime lifeline under a rare arrangement. It was declared a free port for Ethiopian trade.

Ethiopian customs officers operated inside Assab; goods entering or leaving Ethiopia paid no Eritrean duties; port and refinery services were settled in Ethiopian birr rather than foreign currency.

An International Monetary Fund (IMF) report from the late 1990s described the system as “mutually advantageous,” noting extended storage periods for Ethiopian cargo — 30 days compared to 15 for other clients. It was, by any measure, a model of regional integration.

Politics over economics

The arrangement collapsed not because of fees or restrictions, but because Ethiopia treated the partnership as a zero-sum game — viewing Eritrea’s gain as its own loss.

In the years leading up to the 1998–2000 border war, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF)-led government in Addis Ababa decided to reroute trade away from Eritrea.

Former Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi bluntly articulated the motive: “If we use Assab, both sides benefit. If we don’t, Eritrea gains nothing — Assab will be nothing but a watering-place for camels.”

That decision effectively cut Eritrea off from service revenue and forced Ethiopia to rely on Djibouti, which at the time had limited capacity. The political calculation was clear — to isolate Eritrea economically and secure leverage.

Humanitarian irony

Even during Ethiopia’s severe droughts, the pattern held. In 2002, Eritrea offered its ports of Massawa and Assab to handle international food aid destined for Ethiopia.

Addis Ababa declined. The offer was confirmed by the UN’s humanitarian network (IRIN) and BBC reports at the time.

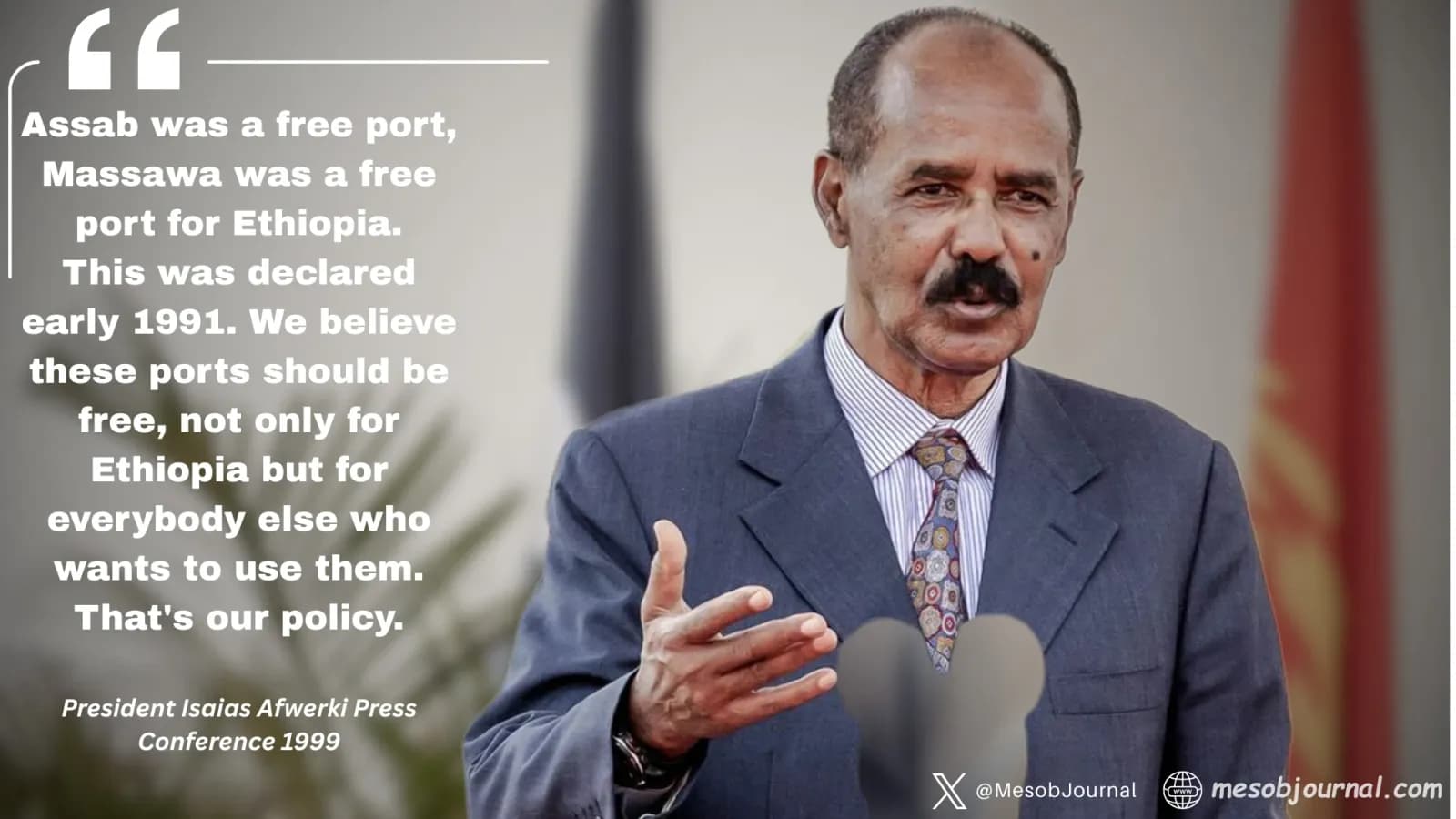

Eritrea’s position, restated repeatedly in regional forums, was that its ports remained open for peaceful trade and humanitarian shipments — provided sovereignty was respected.

Paying more for arrogance

Since then, Ethiopia has invested heavily in Djibouti’s port and rail infrastructure, paying annual service and logistics costs estimated by independent analysts at $1 billion to $2 billion.

Even by conservative measures, the total exceeds $40 billion over three decades — a self-imposed expense that economists say could have been avoided under the earlier Assab arrangement.

“The figures show a long-term structural loss, not caused by geography but by policy of arrogance,” said Mesob Journal trade analyst and author Mr. Gustason. “Ethiopia chose to pay more to keep politics intact — better a scapegoat than a reckoning with its own ethnic divisions.”

The record remains

Documents from the Permanent Court of Arbitration later confirmed that Eritrea never revoked Ethiopia’s port privileges until fighting began. The tribunal noted that Assab “remained available for Ethiopian cargo” during the initial period of tension.

In other words, the gates were open. It was Addis that closed them.

A costly detour

Three decades on, Ethiopia still moves almost all of its trade through Djibouti. Lately, top officials in Addis Ababa have begun speaking again about “access to the sea” — not in the language of partnership, but in the language of illegal possession. The tone is unmistakable: what was once framed as cooperation is now spoken of as a right, even an inheritance.

Yet the facts haven’t changed. Eritrea never closed the door. Ethiopia walked away and now wants to rewrite the story.

Ethiopia’s sea problem was never the map. It was the mindset.

Related stories

Abiy Rewrites the Rift With Eritrea—Yemane Calls It a Cover Story

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed stood in Ethiopia’s parliament today and tried a quiet pivot: the standoff with Eritrea, he argued, isn’t really about Ethiopia’s campaign for “access to the sea.” It’s about alleged Eritrean crimes during the Tigray war—claims he bundled into a single s

Eritrea Draws a Legal Red Line on Ethiopia’s “Sea Access” Drumbeat

On Thursday Jan. 30 2026, Eritrea's Information Minister Yemane G. Meskel cut through weeks of Addis Ababa’s noisy “sovereign sea access” messaging with a blunt reminder: access to ports is commerce and transit — not entitlement, not “historical destiny,” and not a blank cheque f

Isaias Afwerki on Abiy Ahmed: War Rhetoric, Optics, and a Hollow State

When President Isaias Afwerki was asked about Ethiopia’s “Two Waters” rhetoric and escalating war language on January 12, 2026, his response was unusually curt. The question, he said, should not even have been asked. That dismissal wasn’t evasion. It was diagnosis. Afwerki redu

Abiy Ahmed’s Strategic Isolation Is Now in Writing

What Addis Ababa has spent two years denying is now staring it in the face—on White House letterhead. The January 16 letter from Donald Trump to Abdel Fattah el-Sisi isn’t just about mediation. It’s a signal. Clear, deliberate, and consequential. Washington is aligning itself